On May 31, 1950, the Virginia & Truckee Railroad made its final run. The rail line, which had started operating in 1869, had been on life support for more than two decades.

In the 1940s, the owners began to sell off the most historic equipment, with much of the rolling stock going to Hollywood studios to be used in westerns. In 1949, the state gave permission for the company to cease operating.

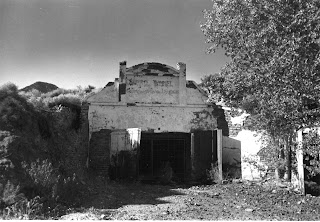

Within a few years, the rails had been pulled up and sold for scrap. Many of the former depot buildings and the maintenance facilities were abandoned or neglected. It appeared that the V&T, as it was known, would become a quaint historic footnote.

That, however, isn’t the end of the story. In the early 1970s, a California businessman and train buff, Robert C. Gray, began gradually rebuilding the V&T route downhill from Virginia City.

By the 1990s, Gray operated a tourist railroad with a vintage steam locomotive (not an original V&T engine) that traveled from a small depot on F Street, just south of the St. Mary's in the Mountains Catholic Church, to the Gold Hill Depot, which Gray helped renovate.

The round trip, 35-minute train ride traveled a little under six miles and passed through several reconstructed tunnels. During the leisurely ride, travelers enjoyed an informative talk as the conductor related Comstock stories and pointed out places of historic interest along the way.

In the early 1990s, V&T enthusiasts along with Storey County, Carson City, and state officials began studying the possibility of reconstructing the historic rail line all the way from Virginia City to Carson City.

A financial study indicated that the railroad was feasible and the non-profit Nevada Commission for the Reconstruction of the V&T Railroad was created to raise money for the project, estimated to cost $25 million when completed.

In 2005, the project picked up steam when the Nevada Department of Transportation awarded a $3.8 million contract to extend the railroad south from Gold Hill. The contract included filling in the Overman Pit, which had blocked previous efforts to lengthen the railroad (the large open pit mine had been dug after the railroad was abandoned).

The Nevada Legislature provided additional funds to help keep the project going while the Department of Transportation donated a railroad bridge formerly used in Southern Nevada for a crossing over U.S. 50, once the rebuilt railroad reaches that point.

The reconstructed railroad will closely follow the original railroad right-of-way between Virginia City and Carson City. It will incorporate the Virginia and Truckee Railroad Company’s 2.5 miles of existing track from Virginia City to the Gold Hill Depot.

From there, it will cross the filled-in Overman Pit and continue through American Flat, a former mining mill district near Silver City, before reaching U.S. 50 near Mound House.

The route crosses the highway and enters the Carson River Canyon area, where it winds along the banks of the river, offering spectacular views. It will conclude its 21-mile route in Carson City. Railroad officials hope that the first leg of the expanded rail line, Gold Hill to U.S. 50, will be completed by 2009.

In the meantime, Gray continues to offer rides on the first portion of the route. His train operates from Memorial Day until the end of October. Cost is $6 for adults, $3 for children 5-12, children under 5 free, and an all day pass is $12. For more information call 775-847-0380.

The V&T’s history is intertwined with the story of Virginia City’s mining industry. Built in 1869, the Virginia & Truckee was the brainchild of banker William Sharon, the Bank of California’s representative in Virginia City.

The 21-mile Virginia City to Carson City leg of the railroad was completed in November 1869, with the Carson City to Reno extension finished in August 1872.

Records show that by the mid-1870s, Virginia City’s mines were so productive that from 30 to 45 trains operated daily on the 55-mile-long railroad, which, because of its winding route became known as the “Very Crooked and Terribly Rough Railroad.”

The V & T’s fortunes began to wane with the decline of mining in the Virginia City area in the 1880s. By the turn of the century, the railroad had shifted its focus from transporting ore to carrying tourists and other passengers.

In 1906, the V & T was extended south of Carson City to Minden. The railroad’s financial situation worsened after 1924, when mining had virtually stopped in Virginia City.

The railroad struggled to stay in business during the next 26 years (with the unprofitable Virginia City to Mound House spur shut down in 1938), losing money in each succeeding year. In 1950, the line was formally abandoned.

But, in the words of Mark Twain, who also spent a lot of time on the Comstock, reports of its death were greatly exaggerated.