The best place to look at Emerald Bay is from Eagle Falls. In fact, from Eagle Falls every view of Lake Tahoe is magnificent. And, if you toss in the sublime beauty of the falls themselves, you’ve got a spectacular outing.

Eagle Falls, which overlooks Emerald Bay, is another of those special scenic places that you discover just when you start feeling jaded about Lake Tahoe.

The falls are easy to reach, located adjacent to Highway 89. To get there, you basically park in one of the nearby lots, then walk toward the sound of rushing water.

Eagle Creek pours out of the trees from the westside of the highway and flows under the road. The creek feeds into several small pools before spilling over a steep, granite bench to Lake Tahoe below.

The creek’s waters are cold and fresh; making the shallow pools inviting but chilly. From the top, you can look over the edge and see the creek waters rolling down the hillside. In the spring and summer, there is usually enough water that the falls form a three-tiered cascade.

If you walk down the trail leading to nearby Vikingsholm (one mile from the parking lot), you can actually reach the falls from below, which offers an equally satisfying experience.

Just beyond the ranger office (a brown log cabin), there is a short trail, about two-tenths of a mile, which leads to the bottom of the falls. The trail passes through firs and cedars, then ascends through aspen and alder, adjacent to the creek.

Stairs lead you along the creek to a clearing at the base of Eagle Falls, which is a popular picnicking spot.

If you park in the small lot on the opposite side of Highway 89 from Eagle Falls, you can find several trails leading to other, equally scenic locations.

For instance, there’s an extremely short walk (half-mile from the parking lot) that leads to Upper Eagle Falls. This hike crosses Eagle Creek and includes a brief climb to a rock bench that offers a marvelous view of Tahoe from a slightly higher elevation.

The trail is well-used and easy. It passes through a grove of aspens, which are particularly colorful in Fall, when the leaves turn gold.

The hike requires an easy climb on rock steps, which leads to a large, metal bridge that spans Eagle Creek. After crossing, the trail leads to a smooth, rock clearing that offers yet another great view of the lake.

Additional good views can be found above this spot on granite perches located along the trail.

From here, the trail continues for another mile to picturesque Eagle Lake, located within the Desolation Wilderness. The latter is a unique, undeveloped expanse, located west of Lake Tahoe, that is a popular hiking region.

If you plan to enter the Desolation Wilderness area, you must obtain a permit at the trailhead at the parking lot. Because of its popularity, there is a limit on the number of people allowed to spend the night in the wilderness (700 per day). It’s a good idea to contact the Forest Service in advance if you’re planning an overnight stay.

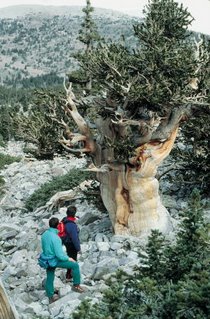

The Desolation Wilderness earned its rather ominous name because of its vast stretches of exposed granite and barren, windswept peaks. Despite the name, however, the wilderness area is actually a very beautiful and scenic region.

You’ll find the wilderness isn’t all that wild or remote—chances are you’ll encounter plenty of people on its trails. But it’s worth a visit because within its 63,960 acres you can find about 130 lakes and lots of remarkable, glacier carved scenery.

For more information about the Desolation Wilderness go to www.fs.fed.us/r5/eldorado/wild/deso/.

To obtain a permit in advance, contact the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit, 35 College Drive, South Lake Tahoe, CA 96150, 530-543-2600 or pick up a permit at the Taylor Creek Forest Service Visitor Center on Highway 89, 530-543-2674.