There’s a place at Lake Tahoe where you can look eye-to-eye with fish without getting wet.

The place is the Stream Profile Chamber at Lake Tahoe’s Taylor Creek Visitor Center on the lake’s southern shore. The center is located on Highway 89, about three miles north of the intersection of U.S. 50 and Highway 89.

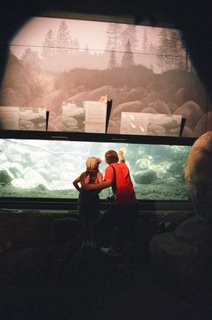

The Stream Profile Chamber offers the chance to get an underwater view of one of Taylor Creek, one of the many natural streams that flows into Lake Tahoe.

Floor-to-ceiling glass windows in a special, underground exhibit present a one-of-a-kind view of the creek, which is home to trout, Kokanee Salmon, crayfish, frogs and a variety of water insects.

In addition to offering a fish-eye perspective, the Stream Profile Chamber contains a large mural depicting the four seasons of Taylor Creek and displays describing the various fish, plants and animals found in or around the creek.

The chamber, however, is only part of the reason to visit the Taylor Creek facility, which is operated by the U.S. Forest Service. The complex also includes an information desk manned by forest service rangers and a small gift shop.

Additionally, the Lake of the Sky Amphitheater, an outdoor stage with seating is a popular site for special nature programs offered by the rangers.

In the meantime, you can also enjoy one of the ranger-led informal “Patio Talks,” offered daily in the summer months. The brief presentations cover a variety of topics such as Lake Tahoe plants and animals or the region’s Native Americans.

There are also several short trails that wind through the area around the visitor center.

The Rainbow Trail is a half-mile paved loop route that leads to the Stream Profile Chamber. This trail starts at the visitor center and soon leads into a small grove of quaking aspen.

Interpretive signs along the way describe the natural history of the area. At about the half-way point, you reach Taylor Creek, a natural trout and salmon spawning stream.

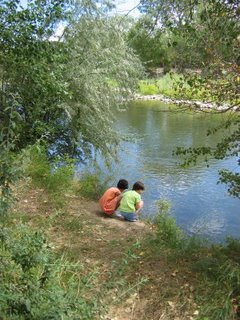

The creek is peaceful and beautiful as it meanders through the trees, heading toward Lake Tahoe. A wooden walkway has been built over the stream and affords a nice place to just stand and enjoy the lush surroundings.

The month of October is the time of year the fish are most active and when you can see several varieties of fish swimming in deeper pockets of water in the creek.

The trail leads into the Stream Profile Chamber. Exiting out the other side, the trail continues into the trees before winding its way through green meadows and over several smaller streams.

If you look behind you on the trail, you can see majestic Mount Tallac in the background (it’s the mountain with the snow that is shaped like a giant cross on its southern face).

The other main developed trail is Lake of the Sky Trail, which leads from the visitor center down to Lake Tahoe. This half-mile trail includes a wooden wildlife viewing deck, which offers nice views of the Taylor Creek marsh and meadow.

The deck also boasts a colorful, panoramic display that points out many of the plants and animals that live in the area (and where you might see one if you look closely). It is also a popular spot for birdwatchers.

In the summer months, the Taylor Creek Visitor Center and Stream Profile Chamber are open daily from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. There is no admission charge.

For more information contact the Taylor Creek Visitor Center, 530-543-2674.