Ruins of Tybo Schoolhouse

If someone gave awards for endurance to old mining towns, the Central Nevada mining camp of Tybo would be an easy winner.

Unlike many of Nevada's abandoned 19th century mining camps, Tybo, which is located 60 miles northeast of Tonopah, has managed to reach the 21th century with an impressive number of its historic structures intact.

Silver was discovered in the Tybo Canyon area (the name is derived from "tai-vu," the Western Shoshone word for "white man") of Central Nevada in 1866, although large scale mining didn't begin until about six years later with construction of a smelter.

While known as a fairly peaceful camp in its early years, by the mid-1870s it had evolved into three distinctive districts divided by ethnicity (Irish, Cornish and Central European) and had experienced some cultural tensions.

Ironically, one of the few occasions during which the three groups were unified was when they banded together to repel Chinese woodcutters who attempted to settle in the area.

By 1876, Tybo had 1,000 residents and a small commercial district that included five stores, an express office, saloons, three hotels, two restaurants, two liveries, a post office and a newspaper, the Tybo Sun.

The town experienced its first mining slump in 1879. The decline caused mines and the local smelter to shut down and the population soon plummeted to less than 100 people.

By 1880, the newspaper had stopped publishing although a new mill and a brick schoolhouse were built that year.

During the next half-century, Tybo's fortunes rose and fell according to the amount of activity supported by local mines. Revivals occurred in 1901, 1905, 1917 and 1925.

The latter boom was fairly significant resulting in construction of a 350-ton mill and a new smelter, which sustained the town for the next 12 years. In the early 1930s, the town counted 75 residents. The post office, which had closed in 1906, was reopened.

Since the end of the last major boom in 1937, Tybo has supported a string of smaller mining operators. As a result, the town has occasional residents and caretakers to watch over the ruins.

To reach Tybo, head east of Tonopah on U.S. 6 for 44 miles to Warm Springs. Continue another 8 miles to the turnoff for Tybo (there is an historic marker near the turnoff). Drive 6.5 miles on a maintained dirt road to the ghost town.

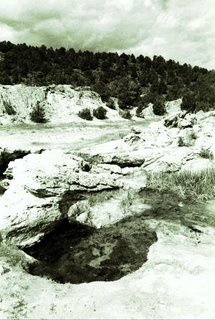

At the mouth of Tybo Canyon, about a mile from the town site is a small cemetery containing a few stone and wood headstones dating to the late 19th century.

Wandering down the main street of Tybo, you can find plenty of reminders of the town’s rich history, including a few houses that are still in good shape.

Near the town entrance, you encounter the ruins of what appears to have been an old house, its chimney intact but all the other walls gone. All around, poking out of the sagebrush, are the concrete foundations of former mining mill structures and other buildings.

A little farther up the road is the impressive stone Trowbridge Store, constructed in the late 19th century. Originally a cash and credit store, it later served as a recreation hall for miners.

Despite years of neglect, it is in remarkably good shape with most of its roof intact and glass still in some of the windows.

Opposite the store are remains of more recent mining operations including a large, metal headframe and assorted scraps of wood, metal and wire.

Up the canyon from the store are a series of wooden structures that date to the 1930s revival, which have been preserved. One is a large bunkhouse while others are smaller houses. Additionally, on the hillside is a sod-roof house constructed using thick railroad ties.

Continuing up the canyon, you pass another large, metal headframe, several wooden buildings and an abandoned truck as well as additional brick walls and foundations.

About a half-mile up the canyon from the town center are the picturesque brick remains of the old schoolhouse built in 1880.

A special treat for those with high clearance, four-wheel drive vehicles is a trip to Tybo’s charcoal kilns. Located four miles northwest of the town via a very steep and rocky road, the 30-foot high, beehive-shaped kilns, which are in good condition, were built in 1874 of native stone.

A good source of information about Tybo is Shawn Hall’s excellent book, “Preserving the Glory Days: Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of Nye County, Nevada,” which is available in local bookstores.